Are Fund Companies Becoming Invisible To Investors?

/ TweetWhat if fund companies have been going about this all wrong?

What if the decision to focus on distribution as opposed to end-users has been a mistake?

What if years of business-to-business brand-building should have been directed at building a consumer brand?

What’s the future for product manufacturers whose users don’t know their names?

These are a few questions raised by research released Monday by Hearts & Wallets, a financial research platform for consumer savings and investing insights working with its database of 5,500 U.S. households augmented by focus group work.

“In a grave strategic error, investment product managers have allowed their offerings to become commoditized,” Laura Varas, Hearts & Wallets partner and co-founder, said.

Varas gets to this conclusion by pointing to data that shows a decline in product awareness across all lifestages. At the same time, awareness of asset allocation—something distributors provide—is increasing.

In 2010, 76% of U.S. households knew what investment products they owned.This year, 66% do—a 10 percentage point drop in five years.

The study Product Trends: Ownership, Allocations & Competitive Metrics, whichdetails product ownership trends and opportunities within all lifestage, wealth and age segments, finds that only 54% of the Mass Market could say what types of investment products—mutual funds, ETFs, individual bonds etc.—they own. That’s down 14 points from 68% in 2010.

“This trend is yet another sign of how product manager attentiveness to distributor needs, while ignoring consumers, has allowed retail financial distributors to gain the upper hand in satisfying the needs of the ultimate decision-makers–consumers,” says the press release headlined “Wake-Up Call for Investment Product Managers.”

Oh and also, the firm adds, “the loss of power among manufacturers is exacerbated by the white labeling trend in the defined contribution space. Investment menus are shifting from manager-branded portfolios to generically named options in which money management firms are virtually hidden from participants.”

Meanwhile, Distribution Awareness Is High

“We believe it behooves major investment companies for consumers to be aware whether or not they are shareholders, even if the products were selected by an advisor,” said Hearts & Wallets.

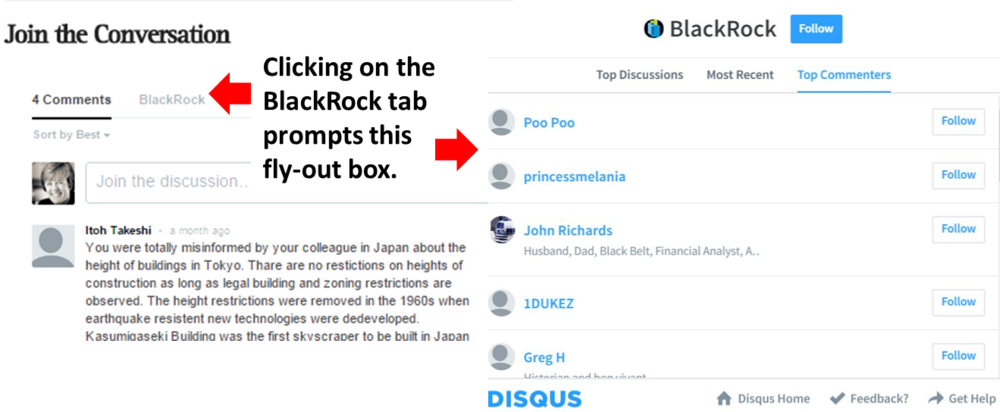

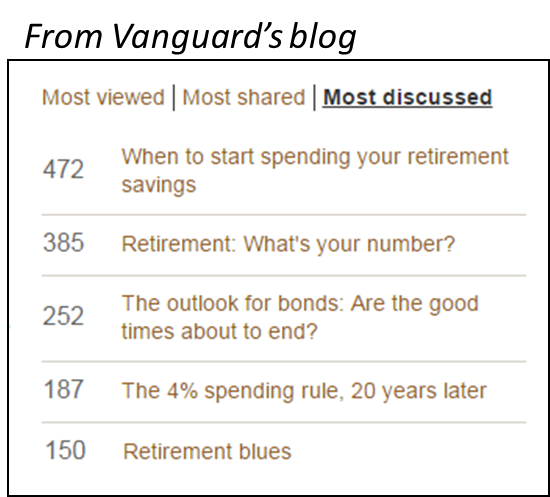

The firm measures this with a Shareholder Awareness score.Vanguard and Fidelity have the most aware shareholders—two-thirds of all shareholders are certain that they are those firms' shareholders. Among purely third-party distributed funds, American Funds leads with a 50% awareness score followed by BlackRock, which has built its score up to 47% from 41% in 2011.

By contrast, 90% of consumers nationally can answer questions about at least one “store”—which is how Hearts & Wallets refers to retail and defined contribution providers that work directly with investors. Just as a Cuisinart blender is available from Bloomingdale's, an American Funds fund might be available from an Edward Jones store or a BlackRock product from the Fidelity store, it explains to focus groups.

The focus group discussions yielded additional troubling insights.

"Participants said they once had expectations for product, but no longer did. And they said they felt most products are the same; products are not perceived as adding as much value as stores," the firm reports.

Even for a third-party distributed fund company, an “extreme degree of disconnection with the consumer” has many disadvantages, according to this explanation from Hearts & Wallets:

- It puts the product managers entirely at the mercy of the “store.”

- It deprives the consumer of knowing that the manager cares about them; many, if not all, of the managers care deeply about their shareholders.

- It deprives product managers of the opportunity to engage with people who are aware of, and presumably interested in, their brand.

Making The Invisible Visible

On the flipside, marketers could no doubt list several arguments in favor of having a strong connection with users of their products.

Think of the legendary "Intel Inside" branding campaign that dates back more than 20 years. Its success in promoting the importance of a branded semiconductor chip (a commodity if there ever was one) in other manufacturers' computers powerfully drove sales and built brand loyalty.

Intel Inside inspired multiple subsequent “ingredient branding" efforts—what marketing professor Philip Kotler referred to as “making the invisible visible.”

You and your firm may want to review the Hearts & Wallets data. See whether it piques your curiosity about the level of your shareholder/investor awareness and its potential impact on your prospects for growth. The research prompted the following random thoughts from me this week.

The role of the relationship. As fascinating as I find the work and the conclusions, Hearts & Wallets' comparison of retail investment product distribution to consumer products and stores isn’t apples to apples. Toothpaste isn’t sold by anyone who seeks to have a relationship with the buyer. There’s a difference between the context of a consumer product transaction and an investment product selected for an outcome-oriented investment portfolio.

That said, I'm reacting to what I’ve seen that the firm has shared publicly. There’s more in the full study, which also includes “insight into innovative product solutions to help product manufacturers regain some balance with distributors.”

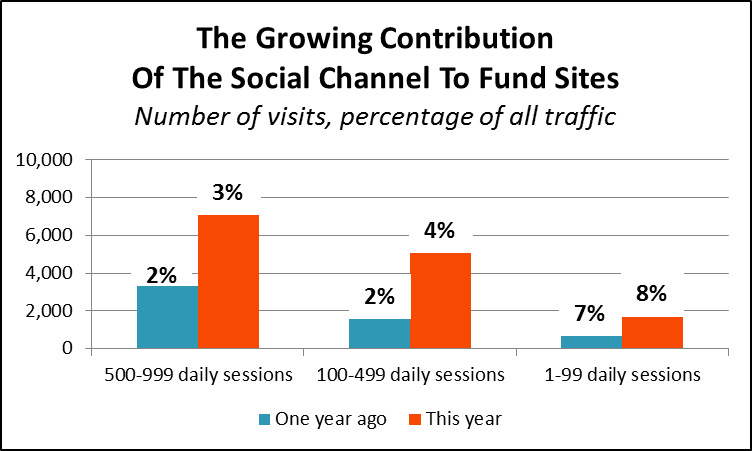

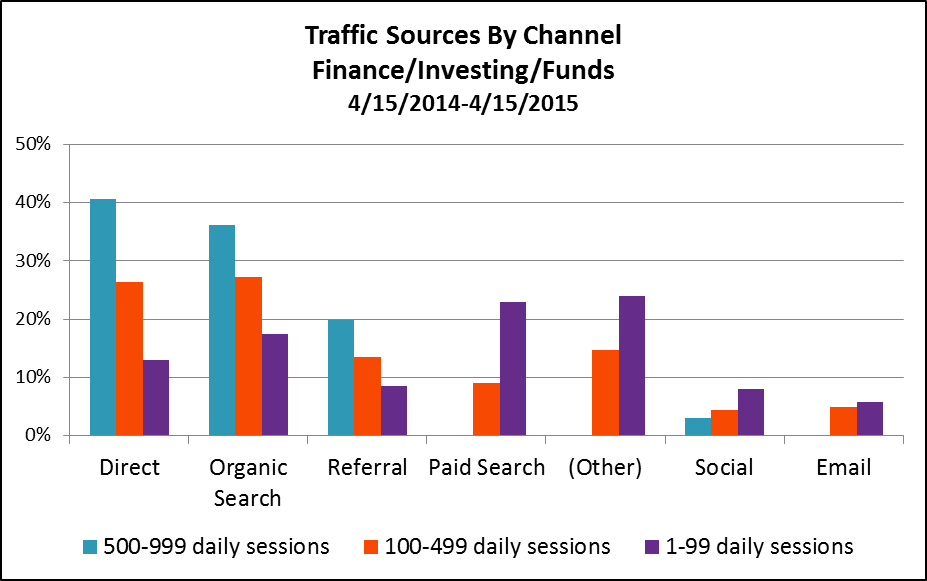

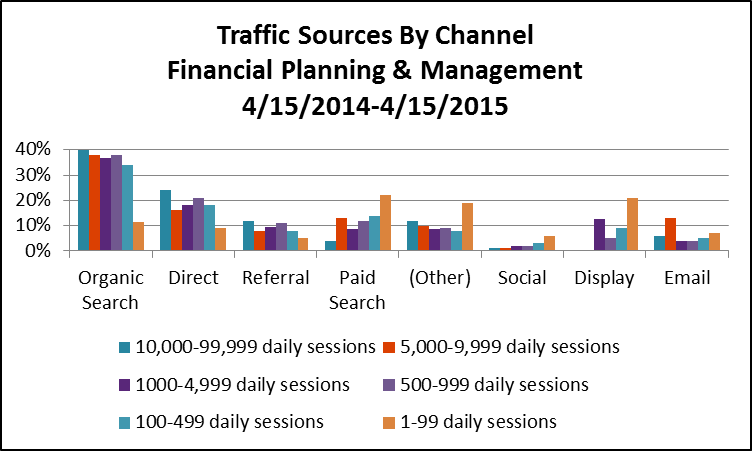

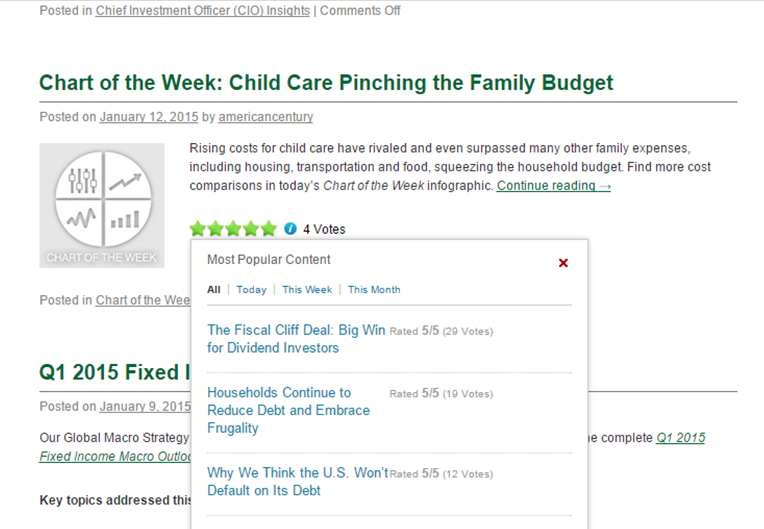

Content requires distribution, too. Embedded in asset managers’ reliance on others for product distribution is a reliance on others for content distribution. Every brand needs to distribute their content but investment brands especially so.

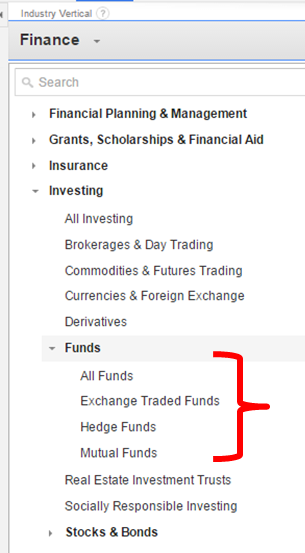

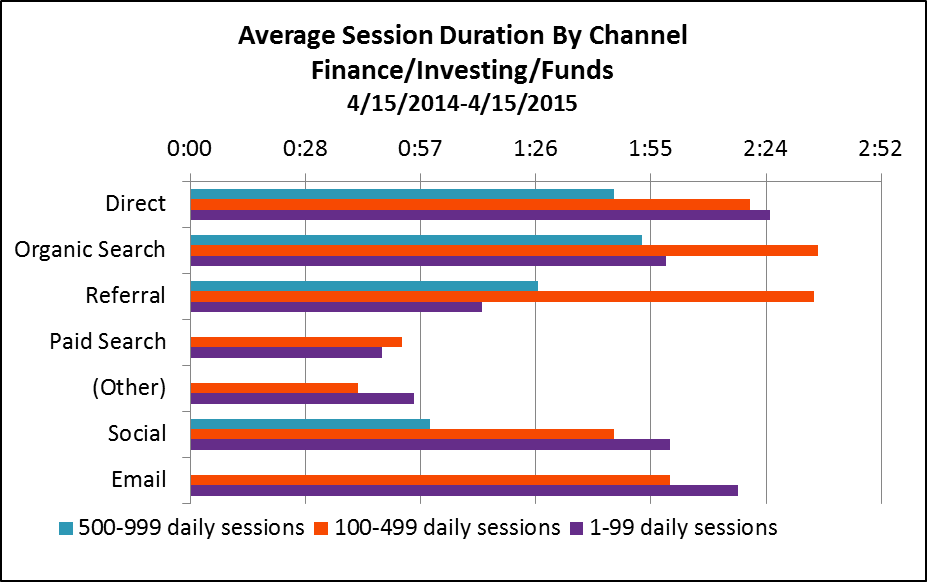

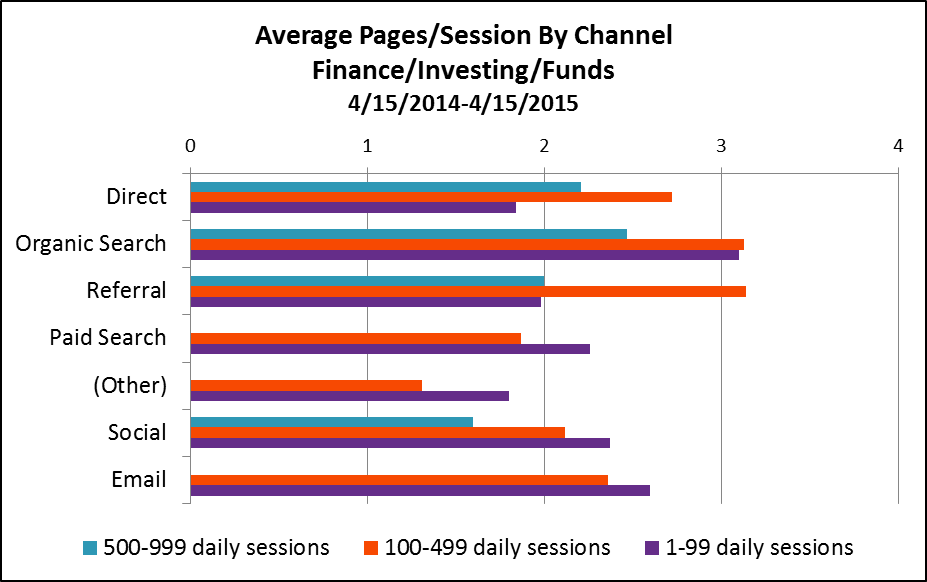

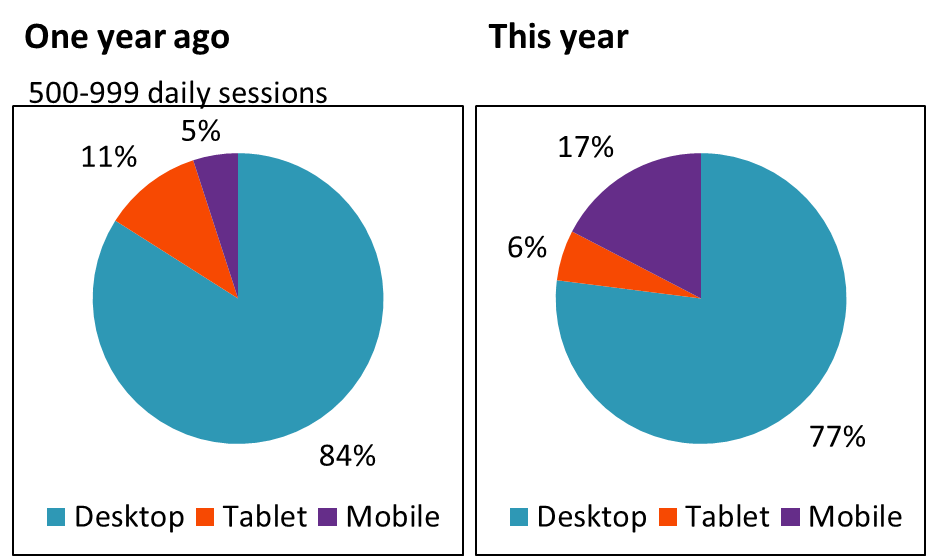

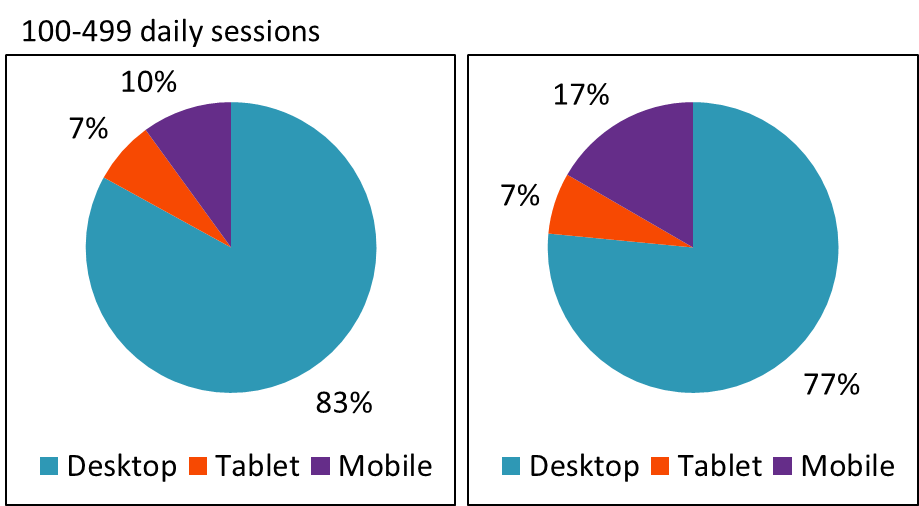

As I’ve commented on previously, mutual fund and ETF sites are product manufacturers’ sites. Their full product specs include information that other sites won’t. But, most product-related traffic goes to distributors’ and others’ domains.

It's just a consequence of today’s business model that when using thought leadership and other content to raise awareness and to demonstrate relevance, asset managers rely on others’ platforms to reach others’ audiences. As with product distribution, this makes firms dependent, can be costly and complicated, and subordinates the fund company brand.

A two-track approach. Let’s suppose that that you find a slide in your retail investor awareness and your firm is determined to reverse it. The effort would take at least two tracks: reaching current investors and reaching the public in general.

Together, omnibus accounts and overall intermediary pushback (i.e., who’s relationship is this, anyway?) present practical challenges to the prospect of elevating the brand to current investors. The greater opportunity will be with whatever marketing, media, public and community relations can accomplish.

Hearts & Wallets’ release recalled the 1990s when “high product awareness prompted consumers to seek out products like the Magellan Fund ofFidelity Investments, which was once the world’s best-known mutual fund.” That was the fund managed by iconic manager Peter Lynch.

For 2015—a disruptive time for every piece of retail investing from the products to the distributors/advisors to the users themselves—effective awareness-building would need to go beyond the promotion of a star manager or two.

Budget-busting. Any strategic decision to reach out to the retail investor would be an expensive one across the board. Brand and advertising is already the largest percentage of asset management marketing budgets, according to SwanDog Strategic Marketing benchmarking work. But most firms today focus on media that helps them reach 300,000 financial advisors. Add retail investor-focused ad buys, inbound marketing, analytics, etc. and you are talking big money.

An ETF advantage? This data would seem to temper what we can expect from mutual fund firms that are getting into the exchange-traded fund (ETF) business. Product awareness is a prerequisite to brand loyalty or brand affinity. If awareness is low, the fund company new to marketing ETFs, whether to advisor-assisted or self-directed investors, may be diversifying product lines with less of an advantage than it realizes.

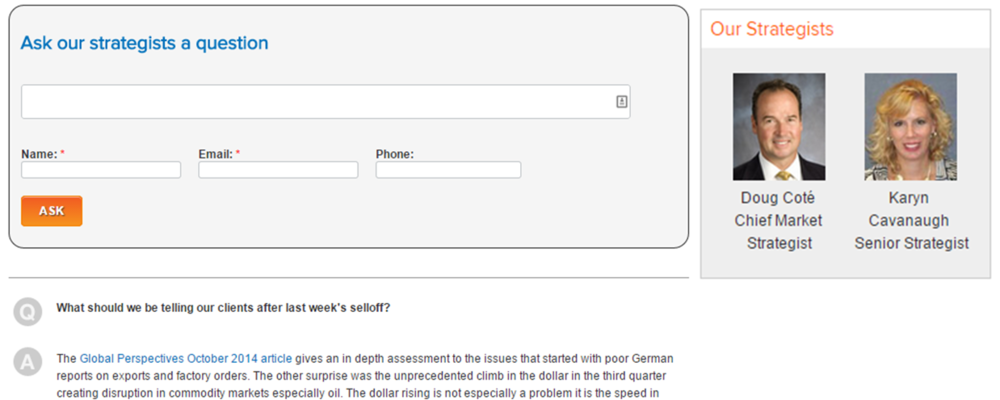

A shift in the power dynamic. Who in the typical intermediary-focused organization best knows the consumer? The people who answer shareholder inquiries and (wait for it) those who've recently become involved with the listening and responding responsibilities of social media. A serious commitment to pay attention to consumers would require the building out of resources, conceivably shrinking—even if just a bit—the influence of the wholesale sales organization.

Regarding social media, specifically: Given access to platforms with millions of consumers, is it a miscalculation for firms to instinctively want to fence off an account or area with content directed at advisors? I'm beginning to wonder.

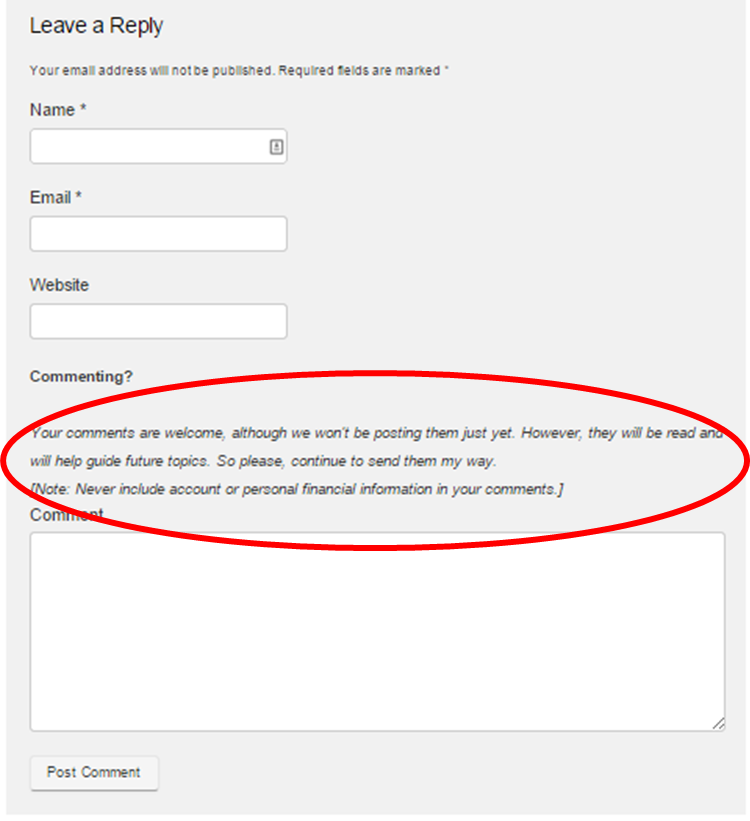

Your thoughts?